Meat-Free Mardis, maximum security and five different flavours of Sorbonne

I had to learn the French university system so now so do you...

Clearly, I have Stockholm syndrome because I’ve decided to attend the most Cambridge-like institution in Paris. Not only is the ENS one of France’s most prestigious schools, but it also has an entire Wikipedia page dedicated to its slang. That’s right, I’ve joined another cult. Goodbye “plodge” and “Mainsbury’s”[1]; hello “Aquarium” and “thurne” (the entrance hall and bedrooms of the ENS respectively).

Who designed this system?

The French higher education system is incredibly perplexing but I will endeavour to explain it as simply as I can. There are universités and there are grandes écoles. Universités can be attended upon leaving high school (lycée) and are open to everyone, whereas grandes écoles are selective and require pupils to take two or three years of classes prépatoires (known as “prépa”) before applying. There are different prépa pathways depending on your subject but one thing unites them all: they are absolutely hellish, perhaps even more intense than Cambridge.

Most grandes écoles specialise in a profession like management or engineering. However, the écoles normales supérieures (there are four, though mine is the original and therefore obviously the best) are just prestigious universities that teach both sciences and humanities.

“It’s very humbling, when you’ve just finished your one course for the day, to hear someone say they now need to go to the Sorbonne for their actual degree”

Confusingly, the ENS is also part of PSL University (Paris Sciences & Lettres) and many students study simultaneously at the ENS and a university. It’s very humbling, when you’ve just finished your one course for the day, to hear someone say they now need to go to the Sorbonne for their actual degree. Likewise, most of the professors are employed by other institutions.

The Paris university system is particularly confusing since the University of Paris was divided, after the May 1968 protests, into thirteen institutions. There are consequently five different universities called the Sorbonne—I know!

They get PAID?

And that’s not all that’s bewildering… At the ENS, there are three main types of student: normalien.ne.s (who get PAID—imagine—to study for four years but must then spend six years in research, teaching or another public sector job), étudiant.e.s (who study for three years but don’t receive the money or obligations) and masterien.ne.s (who join after doing their undergrad somewhere else).

There are also 20 international students each year—ten in the humanities and ten in the sciences—who, again, get PAID to study for three years, after completing an undergrad in their home country. And us, the pensionnaires étranger.ère.s, who get in much more easily!

Campus Fort Knox

That is if you can conquer the school’s rigorous security regime, which demands you use various entrances depending on the hour, sign in visitors regardless of how long they are staying (don’t try talking to the guards if you’re visiting; you will be ignored) and walk through security gates that are far from one-way. These rules very much still apply if you’re on crutches, as one girl in my language classes unfortunately discovered.

Once you’ve penetrated these fortifications, however, the place starts to feel incredibly special. Above the entrance are statues of two women representing the arts and sciences, alongside the medallion of Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom. Further down the Rue d’Ulm is the Panthéon, beside which we sometimes casually eat dinner…

Admittedly, the building has strong hospital vibes. Long corridors form a square around a central courtyard, which is beautifully serene. The hallways are almost indistinguishable but for bright posters advertising various wacky societies, making it incredibly easy to get lost. It doesn’t help that the rooms aren’t numbered but instead named after famous French writers and academics. Nor that it’s impossible to find a map of anywhere but the bottom floor.

Thankfully, the receptionists are incredibly helpful whenever you need to find somewhere so I’ve come to love this infuriating building, which climbs three flours and extends underground, somehow encompassing a gym, bar, theatre, music studio and even a manga library.

The main courtyard is called the Cour aux Ernests (or “Courô” in argot normalien). The busts of famous Frenchmen line its walls, while, at its centre, sits a fishpond. As literally everyone will tell you upon arriving at the ENS, the goldfish are known as “Ernests”, after not one but TWO former directors named Ernest released them to celebrate their new jobs. Courô is a lovely place to study or chat but beware of trying to meet people there. For some reason, the layout of benches and shrubbery makes it impossible to locate your friends.

There are also several incredibly 1930s-looking buildings surrounding this central hub and an entire other campus in the 14th arrondissement. I’ve never been, however, so you’ll have to content yourself with this description of my home in the fifth.

A superior normal school?

Don’t think you’re getting away that easily! As a history student, I feel obligated to explain a little of the backstory behind this confusingly-named institution. The original École normale was established in 1794 during the French Revolution to train secondary school teachers. The idea was to spread the same curriculum across the country—very liberté, égalité, fraternité…

Yet, only a year later, it was closed. The revived institution under Napoleon was smaller and more military in style and, in 1822, it too was abolished for allegedly harbouring liberal ideas. Hence, the ENS has only existed uninterrupted since 1826, first as the École prépatoire and then, after the July Revolution (1830), as the École normale. The “supérieure” bit got added to avoid confusion (that’s right!) after the establishment of écoles normales primaires to train primary school teachers.

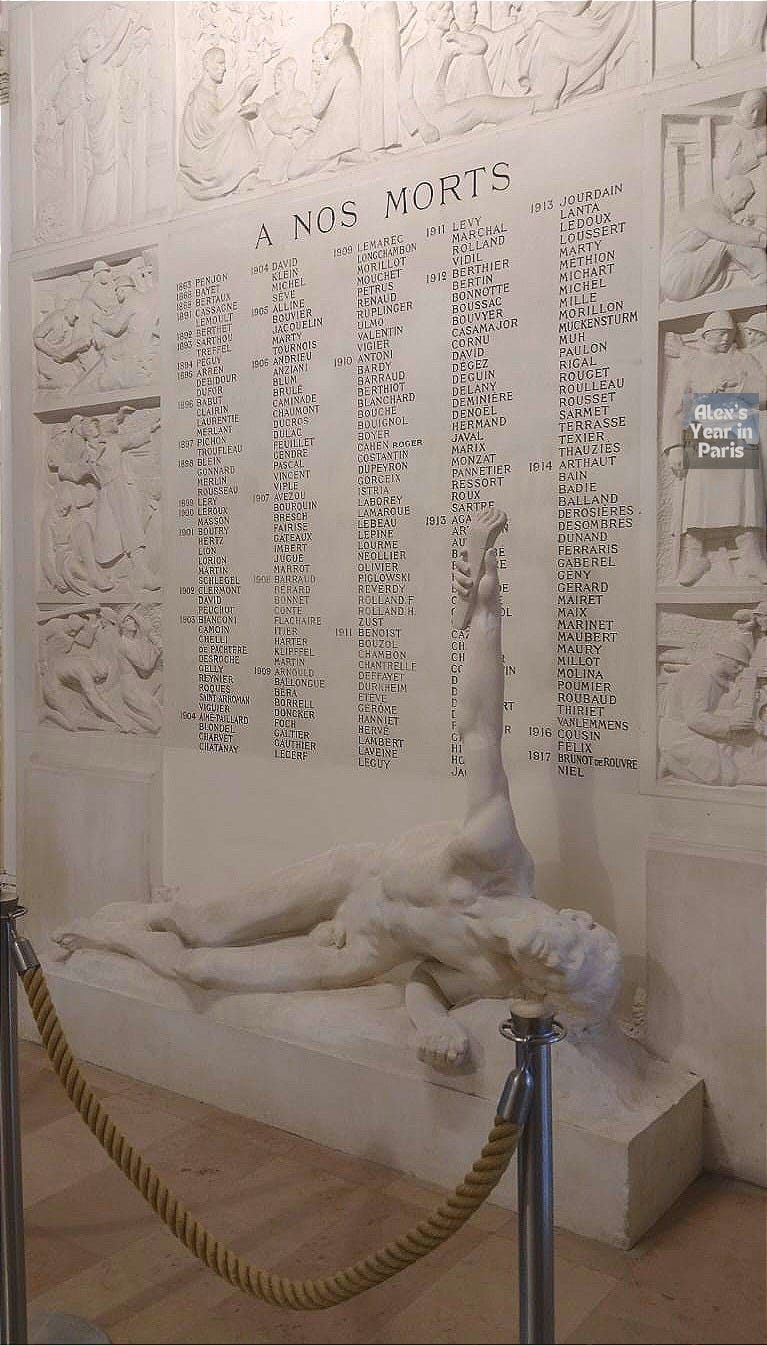

1847 was the year the school moved to Rue d’Ulm, occupying the land of a convent where Victor Hugo used to play as a child. Two huge memorials demonstrate the impact of each world war on the institution, which had to move out of Paris during the Nazi occupation. Since then, the most interesting thing to happen to the school is its occupation by various Maoist sects in 1971.

Practically every French boffin you can think of went to this school, whether that be Louis Pasteur, Assia Djebar, Aimé Césaire or Michel Foucault. However, one person who failed twice to enter the ENS—and they are very proud of this fact—is Emmanuel Macron…

Not quite Magdalene but still…

You’ll be pleased to learn, I’m sure, that the ENS was just as bad at letting in women as Cambridge. Until 1939, women could take the entrance exam but had much less support than men. Indeed, before 1924, schoolgirls had a separate curriculum and, until 1939, mixed schooling was mostly prohibited in France. Nevertheless, 41 women achieved entry to the ENS between 1910-1939.

The school didn’t appreciate this, however, and so banned their access in 1939. Instead, it promised that the École normale supérieure de jeunes filles, founded in 1881 to train teachers for girls’ schools, would offer the same curriculum and degree.

Of course, these qualifications were hardly viewed as equal. One had to wait until 1975, when mixed schooling was made compulsory in public institutions, or 1985, when the two schools merged, to see any progress.

The French Cambridge?

It has the slang. It has the misogyny. Is this just the French Cambridge? Well, there’s one crucial difference. Having worked so hard to get in, ENS students have much less work once they’re here. Not that they give up academics. 85% of students complete a PhD and 75% go into research or teaching. The others take courses on nuclear policy before entering the civil service…

There are 15 departments (as well as a bunch of institutes with confusing-sounding acronyms) and students are encouraged to take courses in several. As a member of a languages faculty back home, it’s depressing to note that ECLA (the ENS equivalent) isn’t a fully-fledged department. Languages are just something that everyone must learn and, if you want to study literature or cinema, then join those departments. What, did you think they only covered French works?

If you’re reading this, Millie, no, you’re not attached to ECLA, whatever you might believe…

Lastly, ENS students are urged to undertake internships and exchanges abroad. In the British Isles, the school has relationships with Oxford, Cambridge and Trinity College, Dublin. They also have links to specific Cambridge colleges, which provide free food and accommodation to students who come to teach us French. In exchange, many of my peers get free accommodation at the ENS, which I’m not at all bitter about!

A familiar conclusion

As is becoming customary for this blog, I will conclude by discussing food. Meals at the ENS are either the most amazing or the most perplexing thing you’ve ever tasted. I’ve had such wonders as pasta and poached egg or chickpea curry plus a kilo of lettuce. Yet, they have only ever come to €4, even with a delicious side or pudding, so I cannot complain.

What I can moan about are the long lines and loud environment, which makes it much harder to understand French. There are three (often indistinguishable) queues, one of which is for vegetarians. I never thought I’d be so disappointed to learn how many vegetarians now live in France!

“I never thought I’d be so disappointed to learn how many vegetarians now live in France”

Whichever counter you choose, your food is unlikely to match its description—but who cares? Alternatively, you could try the cafeteria. However, you get less food there than au Pôt (another ENS term) while paying more money. Finally, there are vending machines to fuel our Orangina addictions and finally make me a coffee person.

I’ll leave you with two helpful initiatives: “Meat-Free Mardis” (I don’t know if they’re actually called that), when all the counters turn vegetarian on Tuesdays, and the leaving out of leftovers to reduce food waste and student poverty.

Plus, another fun fact: French people are obsessed with yogurt.

With just 2,400 students, the ENS is an exclusive and insulated community with MANY idiosyncrasies—ones I hope you have enjoyed learning about today. Next week, I’ll be recounting my two fever-dream-like orientation weeks, full of scary emails, impromptu dance shows and pricey macarons…

Have a question? A complaint? If you’re answer was the former, feel free to leave a comment…

[1] “Porter’s lodge” and “Main Sainsbury’s”