'Soup cures depression' and other things I learned at the ENS

Yes, studying abroad does involve some studying

You walk into your first class at the ENS and the room is packed. And I mean packed. You’re in a tiny, square room on the top floor meant for no more than 15 people. And yet students continue to stream in. There are people perched on tables, crouched on windowsills, strewn across the floor. You’d be forgiven for dismissing the school there and then. What kind of organisation is this?

The source of this confusion is a new system for registering classes. Where previously students submitted a form at the start of term detailing which courses they were taking, it is now enough to simply turn up. Later, a link will be shared to a website called Pegasus, where you can complete your official registration.

Advantages: you can try out classes before settling on your favourites. Disadvantages: teachers have no idea how many students they are teaching before coming to class, resulting in ridiculous room allocations.

Women’s history

Thankfully, when the professor arrives for “Writing the history of women in France and the colonies in the 19th and 20th centuries”, you’re soon escorted to a larger auditorium. She chooses the example of les tondues—women suspected of having relationships with Germans during World War Two who had their heads shaved after Liberation—to illustrate the course’s central themes.

For a long time, the history of women was really the history of activists and femmes d’exception (extraordinary women). The historiography of les tondues demonstrates a growing interest in ordinary women and gender relations rather than women as an isolated category. Since the 1980s, many historians have begun to interrogate the concept of gender itself.

“Since the 1980s, many historians have begun to interrogate the concept of gender itself”

Thus, the shaving of these women’s heads is seen as a way of reasserting traditional gender roles after the disruption of war. Rather than viewing their relationships with Germans as purely sexual, historians are now questioning the reluctance of their predecessors to inscribe women as political actors.

These historiographical developments framed the rest of the course, which covered the French Revolution and Third Republic before moving onto women in France’s colonies. Its direction by a PhD student researching Maghrebi feminists guaranteed this transnational perspective.

She made sure to challenge Western conceptions of Muslim women as weak and oppressed, foregrounding links between activists within the Global South instead of focusing solely on North-North and North-South connections. Another crucial point was that just because a woman doesn’t call herself a feminist or prioritises national over individual liberation doesn’t mean she isn’t one.

French students are accustomed to delivering exposés (presentations) to validate their classes. Thus, we heard excellent analyses of everything from an article by French suffragist Madeleine Pelletier to the memoirs of Egyptian feminist Huda Sha’arawi. The other option was to write an evaluation of a primary or secondary source. Thankfully, as I only needed 15 credits, I avoided the terrifying prospect of producing a speech or essay in French.

Medieval Europe

Not needing to validate all my courses meant I could choose topics outside my comfort zone. At Cambridge, I’ve focused almost exclusively on the 20th century. So, my year abroad seemed the perfect opportunity to cross to the dark side and embrace medieval history.

“My year abroad seemed the perfect opportunity to cross to the dark side and embrace medieval history”

The ENS attempted to cover the entirety of medieval Europe in 24 hours (though it was several lessons before we even reached the Middle Ages). With no PowerPoint accompaniment, the professor lurched between countries and peoples, only stopping the fact vomit to note dates on the board.

It was like no history course I’d taken but it was fascinating (even the parts on church administration—don’t judge). I discovered empires I wasn’t even aware of and fun facts about the origins of things. Did you know the reason we have two ways to write the letter “a” is due to two different Renaissances?

Comparative literature

Ghosts, photography, memory, trauma: the link isn’t immediately obvious but now I’m seeing those themes in everything I read.

The first book covered in Revenant.e.s : Fictions de la mémoire collective (Ghosts: Fictions of Collective Memory) was Anne-Marie Garat’s Photos de familles. While exploring a market in Montmartre, I discovered countless anonymous family photos. Garat used similar finds to construct her novel, inventing the backstories of those featured by painstakingly analysing their postures and expressions.

Frank Auerbach, one of several real figures to inspire characters in W. G. Sebald’s Die Ausgewanderten (The Emigrants), died while I was studying the book so hopefully I’m not cursed… Sebald, an emigrant to the UK, recounts the lives of four other emigrants, including German-British painter Max Ferber (Auerbach) whose parents were killed in the Holocaust.

We also studied Hervé Guibert, an author and photographer who died from AIDS, and a documentary about the Rwandan Genocide, in which interviewees hold up photos of those they lost.

Indeed, one of the course’s best features was its multidisciplinary nature. A guest lecturer discussed efforts to commemorate victims of Argentina and Chile’s dictatorships. This included the most shocking artwork we studied: Protésis by Maria José Contreras. Projecting images of Chilean victims onto her body, the artist extracted milk from her breasts before offering it to the audience—a strikingly material representation of the transmission of collective memory.

Our final lesson was a trip to the Pompidou Centre to see an exhibition celebrating American photographer Barbara Crane. Immediately, I got lost. However, after locating the rest of the class, I found the tour intriguing.

Crane’s work is both documentary and experimental. She photographed people, buildings, objects found on the roadside. But she also experimented with repetition and superimposition to create patterns. My favourite series transformed partygoers into monsters through high-exposure black-and-white photography.

Revenant.e.s could also be validated via exposé. My friends Lucie and Sacha chose to compare Chris Marker’s La Jetée and Annie Ernaux’s The Use of Photography. Another option was creative validation. One student designed storytelling fortune tellers for us to try. Again, I was an auditeur libre (unregistered student).

Methodology

Finally, we arrive at classes I validated. Méthodologie académique à la française sans peine was supposed to explain how to survive French university but ended up being a whole lot more random.

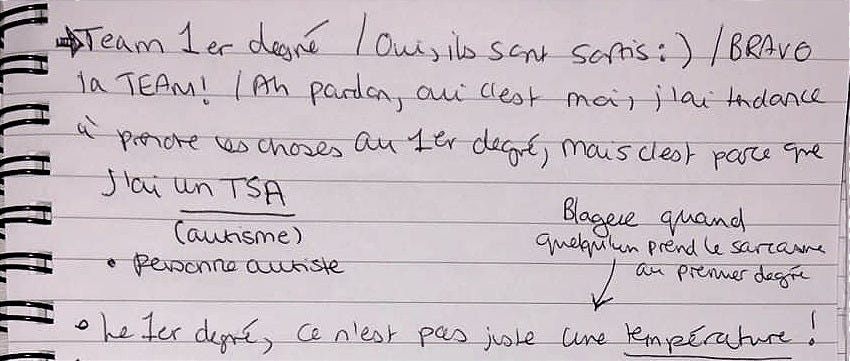

Every lesson began with un point vocabulaire, a single word from which 20 minutes of discussion would emanate. This could lead anywhere from how the French comment on Facebook to their exacting standards of typography (don't be leaving those margins unjustified!).

A particularly memorable session covered ways to avoid seasonal depression: go outside, speak to others, have light in room. It's slightly concerning how little was expected of us.

Once, we were given five minutes to prepare a presentation on a book we’d just been given. Another time, we learned to recite a children’s poem about a snowman. Much of the content was delivered via 80s song, Daniel Balavoine’s Le chanteur reminding us never to begin an email with “je”.

Validating the class meant giving a presentation on the origins of my name (Alexander means “defender of men”—quite a tall order) and writing about a book that left an impression on me (I chose Adam Silvera’s They Both Die at the End because clearly I’ve read nothing since teenagerhood).

Journalism

By far my most demanding class was an atelier d’écriture journalistique (journalistic writing workshop), for which I had to produce an article every two weeks:

A review of Pale Waves’ latest album Smitten. To ensure we focused on analysis and description, we weren’t allowed to give opinions. But to me, this record represents Pale Waves really finding their sound, somewhere between the indie pop of their debut album and pop punk of their last two releases. Though often simple and cliché, it promises a bright future for the Mancunian quartet.

An interview with my history professor about the Gisèle Pelicot rape trial and its media depiction as “historic”.

A portrait of Franco-Malagasy musician Jordan Olympus (Français / English).

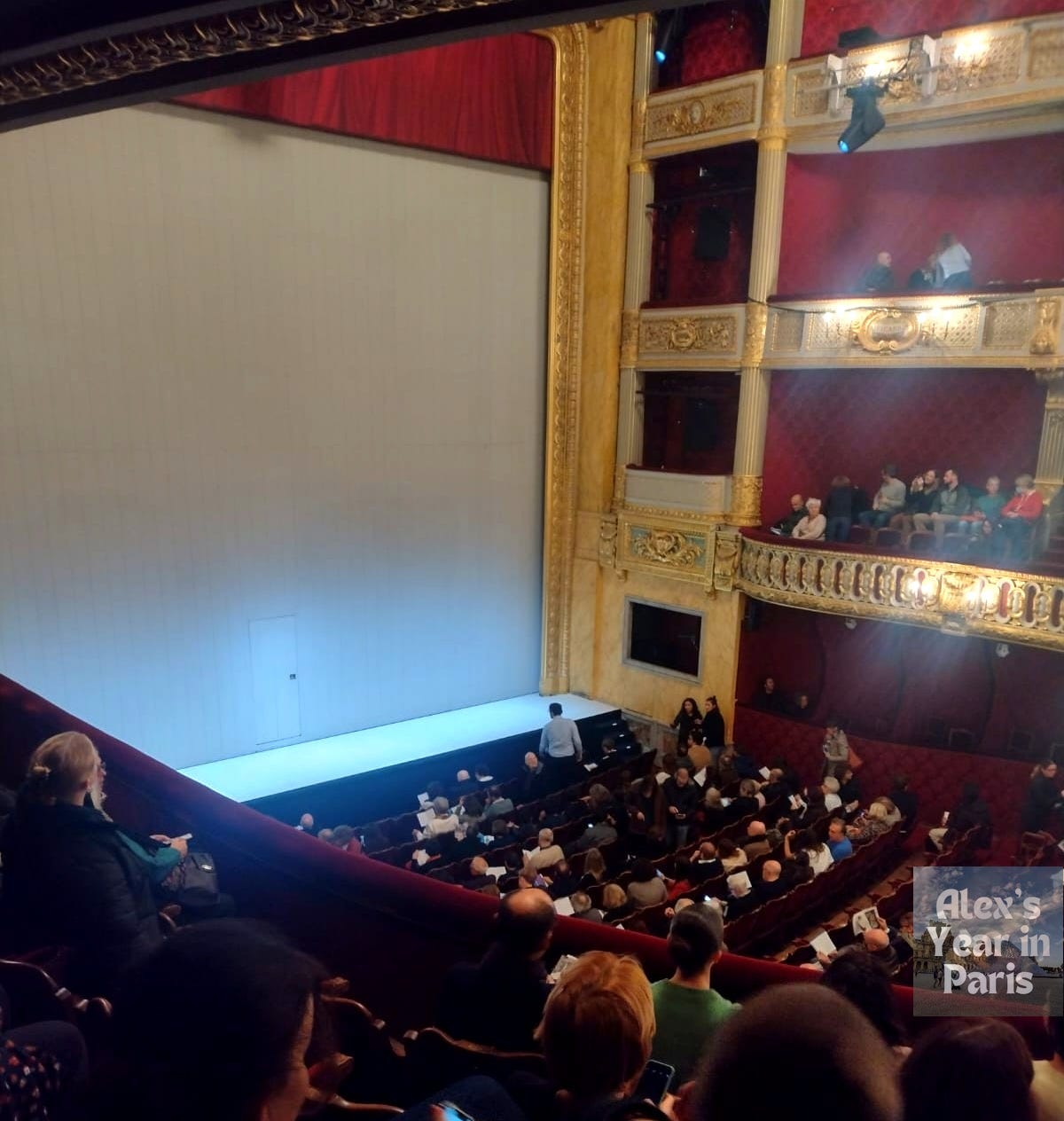

A review of The Seagull at the Odéon. Having obtained tickets through the ENS’s Bureau des Arts, my flatmate Stella and I were escorted to a private box! Laughably expensive carton of water in hand, we enjoyed a spectacular ecological take on Chekhov’s classic (thankfully with subtitles to help us along).

With Sophie Harrison:

A report on the bizarre opening ceremony for the BHV department store’s Christmas decorations, involving lamp-headed puppets and elves abseiling down roofs. “I don't like Marc Lavoine [the musician booked for the event], his music or his personality,” admitted one spectator. “It was anticlimactic,” agreed another.

An analysis of the spread of South Korea’s 4B movement to America following Donald Trump’s re-election. While fascinating, it was impossible to find anyone who knew about it to interview. So, if you’re unaware, “4B” means “4 Nos”: no marriage, children, sex or dates with men.

As an aspiring journalist, the course was invaluable. Despite consisting entirely of international students, the class was marked to professional standards, resulting in VERY harsh feedback. You never knew what to expect: one minute, you were having your article critiqued line-by-line in front of the whole class; the next, you were in the courtyard pestering students for their opinions on Beyoncé and Taylor Swift…

The ENS’s high opinion of itself means all classes are worth six credits. Consequently, I was doing much less than friends at other universities. And I had no exams!

I could’ve done even less but I chose one course each day to ensure I was always practicing my French.

Once I’d gotten used to two-hour classes (don't complain to French students about this; they've had them since secondary school), I found them wide-ranging, stimulating and refreshingly outside my comfort zone—if occasionally rather random and intense.

Hopefully, studying abroad will reduce the shock of returning to Cambridge in October…

Lastly, a definitive ranking of Parisian libraries:

4. ENS Humanities Library: plenty of seats but the melodious accompaniment of construction noises

3. ENS Sciences Library: much more tranquil but the distinct feeling of being an imposter

2. Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève: stunning 19th-century building but impossible to find a seat

1. Bibliothèque Sainte-Barbe: modern, equally difficult to find a seat despite numerous floors but little need to venture further than the café